§ 2. Intervals

In what follows we shall frequently use the concept of an event. An event is described by the place where it occurred and the time when it occurred. Thus an event occurring in a certain material particle is defined by the three coordinates of that particle and the time when the event occurs.

It is frequently useful for reasons of presentation to use a fictitious four-dimensional

space, on the axes of which are marked three space coordinates and the time. In this space events are represented by points, called world points. In this fictitious four-dimensional space there corresponds to each particle a certain line, called a world line. The points of this line determine the coordinates of the particle at all moments of time. It is easy to show that to a particle in uniform rectilinear motion there corresponds a straight world line.

We now express the principle of the invariance of the velocity of light in mathematical form. For this purpose we consider two reference systems and moving relative to each other with constant velocity. We choose the coordinate axes so that the axes and coincide, while the and axes are parallel to and ; we designate the time in the systems and by and .

Let the first event consist of sending out a signal, propagating with light velocity, from a point having coordinates in the system, at time in this system. We observe the propagation of this signal in the system. Let the second event consist of the arrival of the signal at point at the moment of time . The signal propagates with velocity ; the distance covered by it is therefore . On the other hand, this same distance equals . Thus we can write the following relation between the coordinates of the two events in the system:

The same two events, i.e. the propagation of the signal, can be observed from the system:

Let the coordinates of the first event in the system be , and of the second: . Since the velocity of light is the same in the and systems, we have, similarly to (2.1):

If and are the coordinates of any two events, then the quantity

is called the interval between these two events.

Thus it follows from the principle of invariance of the velocity of light that if the interval between two events is zero in one coordinate system, then it is equal to zero in all other systems.

If two events are infinitely close to each other, then the interval between them is

The form of expressions (2.3) and (2.4) permits us to regard the interval, from the formal point of view, as the distance between two points in a fictitious four-dimensional space (whose axes are labelled by , , , and the product ). But there is a basic difference between the rule for forming this quantity and the rule in ordinary geometry: in forming the square of the interval, the squares of the coordinate differences along the different axes are summed, not with the same sign, but rather with varying signs.†

As already shown, if in one inertial system, then in any other system. On

† The four-dimensional geometry described by the quadratic form (2.4) was introduced by H. Minkowski, in connection with the theory of relativity. This geometry is called pseudo-euclidean, in contrast to ordinary euclidean geometry.

the other hand, and are infinitesimals of the same order. From these two conditions it follows that and must be proportional to each other:

where the coefficient can depend only on the absolute value of the relative velocity of the two inertial systems. It cannot depend on the coordinates or the time, since then different points in space and different moments in time would not be equivalent, which would be in contradiction to the homogeneity of space and time. Similarly, it cannot depend on the direction of the relative velocity, since that would contradict the isotropy of space.

Let us consider three reference systems , , , and let and be the velocities of systems and relative to . We then have:

Similarly we can write

where is the absolute value of the velocity of relative to . Comparing these relations with one another, we find that we must have

But depends not only on the absolute values of the vectors and , but also on the angle between them. However, this angle does not appear on the left side of formula (2.5). It is therefore clear that this formula can be correct only if the function reduces to a constant, which is equal to unity according to this same formula.

Thus,

and from the equality of the infinitesimal intervals there follows the equality of finite intervals: .

Thus we arrive at a very important result: the interval between two events is the same in all inertial systems of reference, i.e. it is invariant under transformation from one inertial system to any other. This invariance is the mathematical expression of the constancy of the velocity of light.

Again let and be the coordinates of two events in a certain reference system . Does there exist a coordinate system , in which these two events occur at one and the same point in space?

We introduce the notation

Then the interval between events in the system is:

and in the system

whereupon, because of the invariance of intervals,

We want the two events to occur at the same point in the system, that is, we require . Then

Consequently a system of reference with the required property exists if , that is, if the interval between the two events is a real number. Real intervals are said to be timelike.

Thus, if the interval between two events is timelike, then there exists a system of reference in which the two events occur at one and the same place. The time which elapses between the two events in this system is

If two events occur in one and the same body, then the interval between them is always timelike, for the distance which the body moves between the two events cannot be greater than , since the velocity of the body cannot exceed . So we have always

Let us now ask whether or not we can find a system of reference in which the two events occur at one and the same time. As before, we have for the and systems . We want to have , so that

Consequently the required system can be found only for the case when the interval between the two events is an imaginary number. Imaginary intervals are said to be spacelike.

Thus if the interval between two events is spacelike, there exists a reference system in which the two events occur simultaneously. The distance between the points where the events occur in this system is

The division of intervals into space- and timelike intervals is, because of their invariance, an absolute concept. This means that the timelike or spacelike character of an interval is independent of the reference system.

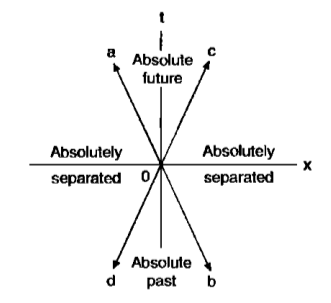

Let us take some event as our origin of time and space coordinates. In other words, in the four-dimensional system of coordinates, the axes of which are marked , , , , the world point of the event is the origin of coordinates. Let us now consider what relation other events bear to the given event . For visualization, we shall consider only one space dimension and the time, marking them on two axes (Fig. 2). Uniform rectilinear motion of a particle, passing through at , is represented by a straight line going through and inclined to the axis at an angle whose tangent is the velocity of the particle. Since the maximum possible velocity is , there is a maximum angle which this line can subtend with the axis. In Fig. 2 are shown the two lines representing the propagation of two signals (with the velocity of light) in opposite directions passing through the event (i.e. going through at ). All lines representing the motion of particles can lie only in the regions and . On the lines and , . First consider events whose world points lie within the region . It is easy to show that for all the points of this region .

In other words, the interval between any event in this region and the event is timelike. In this region , i.e. all the events in this region occur “after” the event . But two events which are separated by a timelike interval cannot occur simultaneously in any reference system. Consequently it is impossible to find a reference system in which any of the events in region occurred “before” the event , i.e. at time . Thus all the events in region are future events relative to in all reference systems. Therefore this region can be called the absolute future relative to .

In exactly the same way, all events in the region are in the absolute past relative to ; i.e. events in this region occur before the event in all systems of reference.

Next consider regions and . The interval between any event in this region and the event is spacelike. These events occur at different points in space in every reference system. Therefore these regions can be said to be absolutely remote relative to . However, the concepts “simultaneous”, “earlier”, and “later” are relative for these regions. For any event in these regions there exist systems of reference in which it occurs after the event , systems in which it occurs earlier than , and finally one reference system in which it occurs simultaneously with .

Note that if we consider all three space coordinates instead of just one, then instead of the two intersecting lines of Fig. 2 we would have a “cone” in the four-dimensional coordinate system , the axis of the cone coinciding with the axis. (This cone is called the light cone.) The regions of absolute future and absolute past are then represented by the two interior portions of this cone.

Two events can be related causally to each other only if the interval between them is timelike; this follows immediately from the fact that no interaction can propagate with a velocity greater than the velocity of light. As we have just seen, it is precisely for these events that the concepts “earlier” and “later” have an absolute significance, which is a necessary condition for the concepts of cause and effect to have meaning.