2. Differentiable manifolds; tangent space

2.1 DEFINITION. A differentiable manifold of dimension is a set and a family of injective mappings of open sets of into such that:

- .

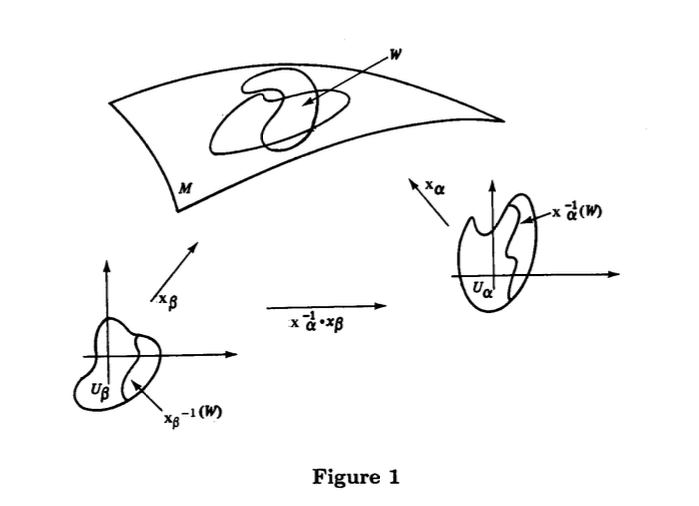

- for any pair , with , the sets and are open sets in and the mappings are differentiable (Fig. 1).

- The family is maximal relative to the conditions (1) and (2).

The pair (or the mapping ) with is called a parametrization (or system of coordinates) of at ; is then called a coordinate neighborhood at . A family satisfying (1) and (2) is called a differentiable structure on .

The condition (3) is included for purely technical reasons. Indeed, given a differentiable structure on , we can easily complete it to a maximal one, by taking the union of all the parametrizations that, together with any of the parametrizations of the given structure, satisfy condition (2). Therefore, with a certain abuse of language, we can say that a differentiable manifold is a set provided with a differentiable structure. In general, the extension to the maximal structure will be done without further comment.

2.2 REMARK A comparison between the definition 2.1 and the definition of a regular surface in shows that the essential point (except for the change of dimension from 2 to ) was to distinguish the fundamental property of the change of parameters (which is a theorem for surfaces in ) and incorporate it as an axiom. This is precisely condition 2 of Definition 2.1. As we shall soon see, this is the condition that allows us to carry over all of the ideas of differential calculus in to differentiable manifolds.

2.3 REMARK A differentiable structure on a set induces a natural topology on . It suffices to define to be an open set in if and only if is an open set in for all . It is easy to verify that and the empty set are open sets, that a union of open sets is again an open set and that the finite intersection of open sets remains an open set. Observe that the topology is defined in such a way that the sets are open and that the mappings are continuous.

The Euclidean space , with the differentiable structure

given by the identity, is a trivial example of a differentiable manifold. Now we shall see a non-trivial example.

2.4 EXAMPLE The real projective space . Let us denote by the set of straight lines of which pass through the origin ; that is, is the set of “directions” of .

Let us introduce a differentiable structure on . For this, let and observe, to begin with, that is the quotient space of by the equivalence relation:

The points of will be denoted by . Observe that, if ,

Define subsets , of , by:

Geometrically, is the set of straight lines which pass through the origin and do not belong to the hyperplane . We are now going to show that we can take the ’s as coordinate neighborhoods, where the coordinates on are

For this, we will define mappings by

and will show that the family is a differentiable structure on .

Indeed, any mapping is clearly bijective while . It remains to show that is an open set in

and that , , is differentiable there. Now, if , the points in are of the form:

Therefore is an open set in , and supposing that (the case is similar),

which is clearly differentiable.

In summary, the space of directions of (real projective space ) can be covered by coordinate neighborhoods , where the are made up of those directions of that are not in the hyperplane ; in addition, in each we have coordinates

where are the coordinates of . It is customary, in the classical terminology, to call the coordinates of “inhomogeneous coordinates” corresponding to the “homogeneous coordinates” .

Before presenting further examples of differentiable manifolds we should present a few more consequences of Definition 2.1. From now on, when we denote a differentiable manifold by , the upper index indicates the dimension of .

First, let us extend the idea of differentiability to mappings between manifolds.

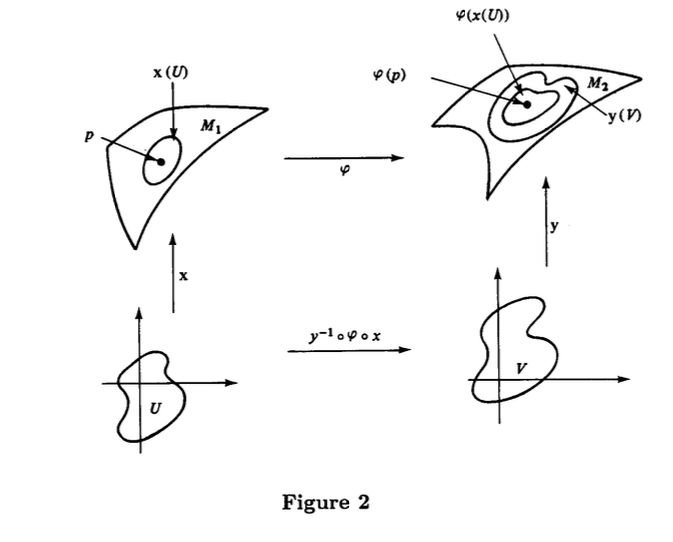

2.5 DEFINITION. Let and be differentiable manifolds. A mapping is differentiable at if given a parametrization at there exists a parametrization at such that and the mapping

is differentiable at (Fig. 2). is differentiable on an open set of if it is differentiable at all of the points of this open set.

It follows from condition (2) of Definition 2.1 that the given definition is independent of the choice of the parametrizations. The mapping (1) is called the expression of in the parametrizations and .

Next, we would like to extend the idea of tangent vector to differentiable manifolds. It is convenient, as usual, to use our experience with regular surfaces in . For surfaces in , a tangent vector at a point of the surface is defined as the “velocity” in of a curve in the surface passing through . Since we do not have at our disposal the support of the ambient space, we have to find a characteristic property of the tangent vector which will substitute for the idea of velocity.

The next considerations will motivate the definition that we

are going to present below. Let be a differentiable curve in , with . Write

Then . Now let be a differentiable function defined in a neighborhood of . We can restrict to the curve and express the directional derivative with respect to the vector as

Therefore, the directional derivative with respect to is an operator on differentiable functions that depends uniquely on . This is the characteristic property that we are going to use to define tangent vectors on a manifold.

2.6 DEFINITION. Let be a differentiable manifold. A differentiable function is called a (differentiable) curve in . Suppose that , and let be the set of functions on that are differentiable at . The tangent vector to the curve at is a function given by

A tangent vector at is the tangent vector at of some curve with . The set of all tangent vectors to at will be indicated by .

If we choose a parametrization at , we can express the function and the curve in this parametrization by

and

respectively. Therefore, restricting to , we obtain

In other words, the vector can be expressed in the parametrization by

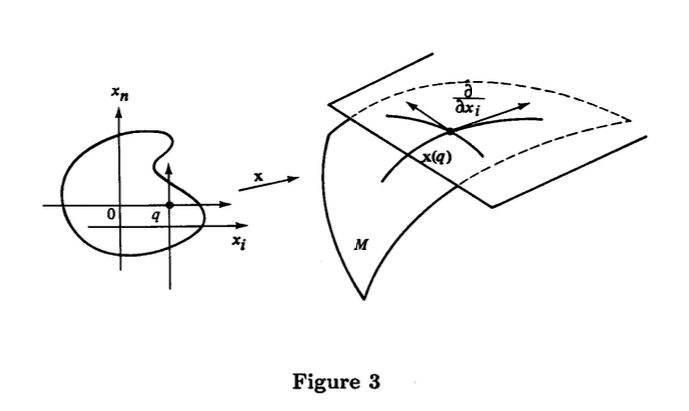

Observe that is the tangent vector at of the “coordinate curve” (Fig. 3):

The expression (2) shows that the tangent vector to the curve at depends only the derivative of in a coordinate system. It follows also from (2) that the set , with the usual operations of functions, forms a vector space of dimension , and that the choice of a parametrization determines an associated basis in (Fig. 3). It is immediate that the linear structure in defined above does not depend on the parametrization . The vector space is called the tangent space of at .

With the idea of tangent space we can extend to differentiable manifolds the notion of the differential of a differentiable mapping.

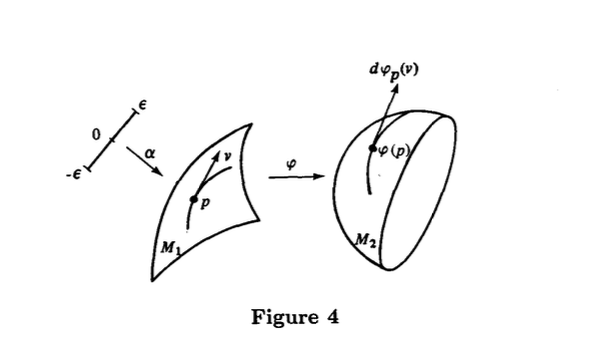

2.7 PROPOSITION. Let and be differentiable manifolds and let be a differentiable mapping. For every and for each , choose a differentiable curve with , . Take . The mapping given by is a linear mapping that does not depend on the choice of (Fig. 4).

Proof. Let and be parametrizations at and , respectively. Expressing in these parametrizations, we can write

On the other hand, expressing in the parametrization , we obtain

Therefore,

It follows that the expression for with respect to the basis of , associated to the parametrization , is given by

The relation (3) shows immediately that does not depend on the choice of . In addition, (3) can be written as

where denotes an matrix and denotes a column matrix with elements. Therefore, is a linear mapping of

into whose matrix in the associated bases obtained from the parametrizations and is precisely the matrix .

2.8 DEFINITION. The linear mapping defined by Proposition 2.7 is called the differential of at .

2.9 DEFINITION. Let and be differentiable manifolds. A mapping is a diffeomorphism if it is differentiable, bijective, and its inverse is differentiable. is said to be a local diffeomorphism at if there exist neighborhoods of and of such that is a diffeomorphism.

The notion of diffeomorphism is the natural idea of equivalence between differentiable manifolds. It is an immediate consequence of the chain rule that if is a diffeomorphism, then is an isomorphism for all ; in particular, the dimensions of and are equal. A local converse to this fact is the following theorem.

2.10 Theorem. Let be a differentiable mapping and let be such that is an isomorphism. Then is a local diffeomorphism at .

The proof follows from an immediate application of the inverse function theorem in .