4. Other examples of manifolds. Orientation

4.1 EXAMPLE (The tangent bundle). Let be a differentiable manifold and let . We are going to provide the set with a differentiable structure (of dimension ); with such a structure will be called the tangent bundle of . This is the natural space to work with when treating questions that involve positions and velocities, as in the case of mechanics.

Let be a maximal differentiable structure on . Denote by the coordinates of and by the associated bases to the tangent spaces of . For every , define

by

Geometrically, this means that we are taking as coordinates of a point the coordinates of together with the coordinates of in the basis .

We are going to show that is a differentiable structure on . Since and , , we have that

which verifies condition (1) of Definition 2.1. Now let

Then

where , , . Therefore,

Since is differentiable, is as well. It follows that is differentiable, which verifies condition (2) of the definition 2.1 and completes the example.

4.2 EXAMPLE. (Regular surfaces in ). The natural generalization of the notion of a regular surface in is the idea of a surface of dimension in , . A subset is a regular surface of dimension if for every there exists a neighborhood of in and a mapping of an open set onto such that:

- is a differentiable homeomorphism.

- is injective for all .

Except for the dimensions involved, the definition is exactly the same as was given in the Introduction for a regular surface in .

In a similar way as was done for surfaces in (M. do Carmo [dC 2], p. 71), it can be proved that if and are two parametrizations with , then the mapping is a diffeomorphism. For completeness, we give a sketch of this proof in what follows.

First, we observe that is a homeomorphism, being a composition of homeomorphisms. Let and put . Let and , and write in these coordinates as

From condition (b), we can suppose that

Extend to a mapping given by

where . It is clear that is differentiable and the restriction of to coincides with . By a simple calculation, we obtain that

We are then able to apply the inverse function theorem, which guarantees the existence of a neighborhood of where exists and is differentiable. By the continuity of , there exists a neighborhood of such that . Note that the restriction of to , is a composition of differentiable mappings. Thus is differentiable at , hence in . A similar argument would show that is differentiable as well, proving the assertion.

From what we have just proved, it follows by an entirely similar argument as in Example 3.6 that is a differentiable manifold of dimension and that the inclusion is an embedding, that is, is a submanifold of .

4.3 EXAMPLE (Inverse image of a regular value). Before discussing the next example, we need some definitions.

Let be a differentiable mapping of an open set of . A point is defined to be a critical point of if the differential is not surjective. The image of a critical point is called a critical value of . A point that is not a critical value is said to be a regular value of . Note that any point is trivially a regular value of and that if there exists a regular value of in , then .

Now let be a regular value of . We are going to show that the inverse image is a regular surface of dimension . From what was seen in Example 4.2, is then a submanifold of .

To prove the assertion we use, again, the inverse function theorem. Let . Denote by an arbitrary point of and by its image by the mapping . Since is a regular value of , is surjective. Therefore, we can suppose that

Define a mapping by

Then

By the inverse function theorem, is a diffeomorphism of a neighborhood of onto a neighborhood of . Let be a cube of center and put . Then maps the neighborhood diffeomorphically onto . Define a mapping by

where . It is easy to check that satisfies conditions (a) and (b) of the definition of regular surface given in Example 4.2. Since is arbitrary, is a regular surface in , as asserted.

Before going on to other examples of differentiable manifolds, we should introduce the important global notion of orientation.

4.4 DEFINITION Let be a differentiable manifold. We say that is orientable if admits a differentiable structure such that:

(i) for every pair , with , the differential of the change of coordinates has positive determinant.

In the opposite case, we say that is non-orientable. If is orientable, a choice of a differentiable structure satisfying (i) is called an orientation of . is then said to be oriented. Two differentiable structures that satisfy (i) determine the same orientation if their union again satisfies (i).

It is not difficult to verify that if is orientable and connected there exist exactly two distinct orientations on .

Now let and be differentiable manifolds and let be a diffeomorphism. It is easy to verify that is orientable if and only if is orientable. If, additionally, and are connected and are oriented, induces an orientation on which may or may not coincide with the initial orientation of . In the first case, we say that preserves the orientation and in the second case, that reverses the orientation.

4.5 EXAMPLE If can be covered by two coordinate neighborhoods and in such a way that the intersection is connected, then is orientable. Indeed, since the determinant of the differential of the coordinate change is , it does not change sign in ; if it is negative at a single point, it suffices to change the sign of one of the coordinates to make it positive at that point, hence on .

4.6 EXAMPLE. The simple criterion of the previous example can be used to show that the sphere

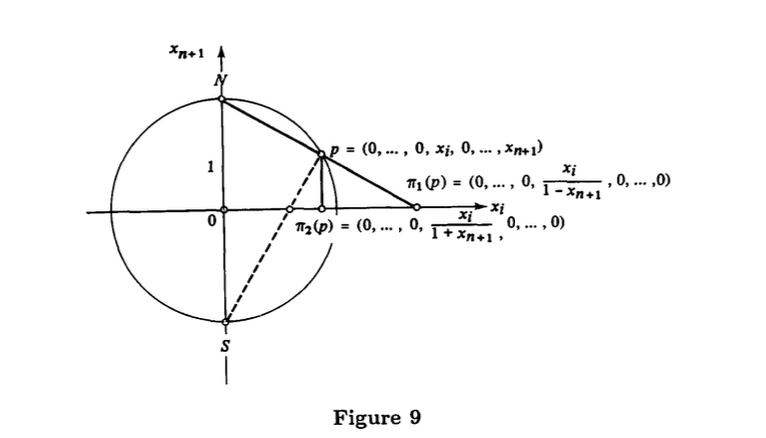

is orientable. Indeed, let be the north pole and the south pole of . Define a mapping (stereographic projection from the north pole) that takes in into the intersection of the hyperplane with the line that passes through and . It is easy to verify that (Fig. 9)

The mapping is differentiable, injective and maps onto the hyperplane . The stereographic projection from the south pole onto the hyperplane has the same properties.

Therefore, the parametrizations , cover . In addition, the change of coordinates:

is given by

(here we use the fact that ). Therefore, the family is a differentiable structure on . Observe that the intersection is connected, thus is orientable and the family given determines an orientation of .

A diagram illustrating the stereographic projection from the unit sphere (represented by a circle) onto the plane (represented by the horizontal axis). The vertical axis is labeled . The origin is labeled 0, and the top point is labeled N (North pole). The bottom point is labeled S (South pole). A point on the sphere is shown, with coordinates . The projection is shown on the positive axis, with coordinates . The projection is shown on the negative axis, with coordinates .

Now let be the antipodal map given by , . is differentiable and . Therefore, is a diffeomorphism of . Observe that when is even, reverses the orientation of and when is odd, preserves the orientation of .

We are now in a position to exhibit some other examples of differentiable manifolds.

4.7 EXAMPLE. (Another description of projective space). The set of lines of that pass through the origin can be thought of as the quotient space of the unit sphere by the equivalence relation that identifies with its antipodal point, . Indeed, each line that passes through the origin determines two antipodal points and the correspondence so obtained is evidently bijective.

Taking into account this fact, we are going to introduce another differentiable structure on (Cf. Example 2.4). For this, we initially introduce on the structure of a regular surface, defining parametrizations

in the following way:

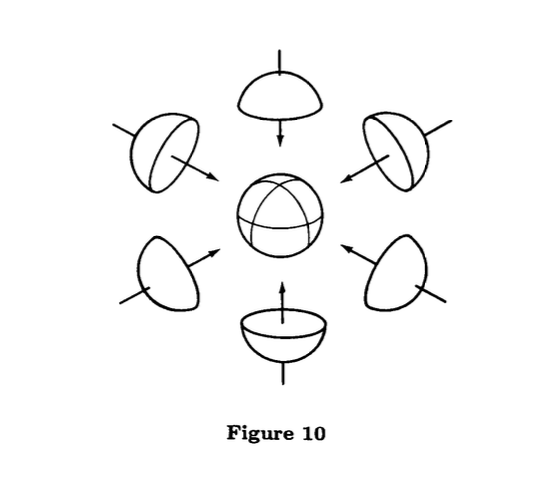

where . It is easy to verify that conditions (a) and (b) of the definition in Example 4.2 are satisfied. Therefore, the family

is a differentiable structure on . Geometrically, this is equivalent to covering the sphere with coordinate neighborhoods that are hemi-spheres perpendicular to the axes and taking as coordinates on, for example, , the coordinates of the orthogonal projection of on the hyperplane (Fig. 10).

Let be the canonical projection, that is, ; observe that . We are going to define a mapping by

Since restricted to is one-to-one, we have that

which yields the differentiability of , for all . Thus the family is a differentiable structure for .

In fact, this differentiable structure and that of Example 2.4 give rise to the same maximal structure. Indeed, the coordinate neighborhoods are the same and the change of coordinates are given by:

which, since and , is differentiable.

As we shall see in Exercise 9, is orientable if and only if is odd.

4.8 EXAMPLE (Discontinuous action of a group). There is a way of constructing differentiable manifolds that generalizes the process above, which is given by the following considerations.

We say that a group acts on a differentiable manifold if there exists a mapping such that:

- For each , the mapping given by , , is a diffeomorphism, and .

- If , .

Frequently, when dealing with a single action, we set ; in this notation, condition (ii) can be interpreted as a form of associativity: .

We say that the action is properly discontinuous if every has a neighborhood such that for all .

When acts on , the action determines an equivalence relation on , in which if and only if , for some

. Denote the quotient space of by this equivalence relation by . The mapping , given by

will be called the projection of onto .

Now let be a differentiable manifold and let be a properly discontinuous action of a group on . We are going to show that has a differentiable structure with respect to which the projection is a local diffeomorphism.

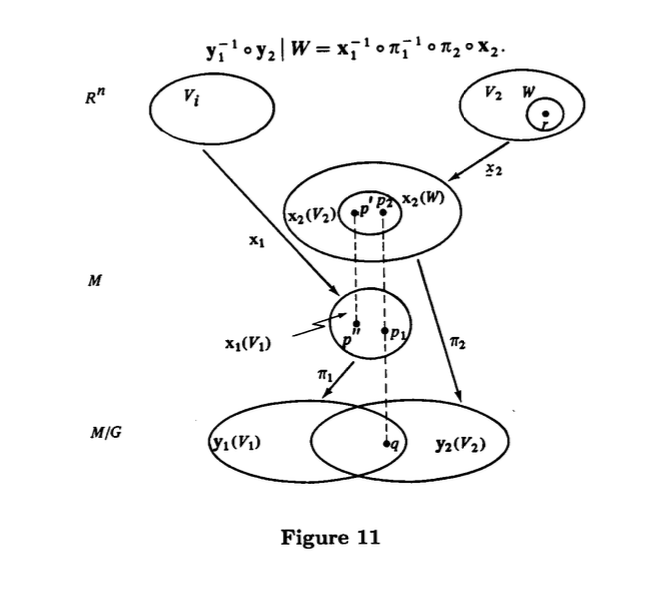

For each choose a parametrization at so that , where is a neighborhood of such that , . Clearly is injective, hence is injective. The family clearly covers ; for such a family to be a differentiable structure, it suffices to show that given two mappings and with , then is differentiable.

For this, let be the restriction of to , . Let and let . Let be a neighborhood of such that (Fig. 11). Then, the restriction to is given by

Therefore, it is enough to show that is differentiable at . Let . Then and are equivalent in , hence there is a such that . It follows easily that the restriction coincides with the diffeomorphism , which proves that is differentiable at , as stated.

From the very way in which this differentiable structure is constructed, is a local diffeomorphism. A criterion for the orientability of is given in Exercise 9. Observe that the situation in the previous example reduces to the present one, by taking and the group of diffeomorphisms of formed by the antipodal mapping and the identity of .

4.9 EXAMPLE (special cases of Example 4.8).

4.9 (a). Consider the group of “integral” translations of where the action of on is given by

Diagram illustrating the relationship between coordinate charts and on , their images and on , and their images and on . The diagram shows the overlap region on and the corresponding overlap region on . The mapping is defined on the overlap region of and on . The relationship between the coordinates is given by the equation above.

It is easy to check that the mapping above defines an action of on , which is properly discontinuous. The quotient space , with the differentiable structure described in Example 4.8, is called the -torus . When , the 2-torus is diffeomorphic to the torus of revolution in obtained as the inverse image of zero of the function

(Cf. M. do Carmo [dC 2], p. 62).

4.9 (b). Let be a regular surface in , symmetric relative to the origin , that is, if then . The group of diffeomorphisms of formed by acts on in a properly discontinuous manner. Introduce on the differentiable structure given by Example 4.8. When is the torus of revolution , is called the Klein bottle; when is the right circular cylinder given by , is called the Möbius band. As we shall see in Exercise 9, the Klein bottle and the Möbius band are non-orientable. In Exercise 6, we shall indicate how the Klein bottle can be embedded in .